Barossa’s story stretches back thousands of years, rooted in the deep cultural connection of the Peramangk, Ngadjuri, and Kaurna people, the land’s first custodians. Their enduring presence has shaped the region’s identity, weaving knowledge, tradition, and connection to country into its very fabric.

The arrival of European settlers in the 1830s marked a new chapter, shaping Barossa into the renowned wine and tourism destination it is today.

Explore Barossa’s journey – its people, traditions, and defining moments – and discover a place where history and progress continue to thrive, side by side.

Pre-1840's - Traditional owners

The Barossa region has been home to First Nations people for tens of thousands of years, far before European settlement. The Peramangk, Ngadjuri, and Kaurna people cared for this land and its resources, building an enduring cultural connection that continues today. Their Dreaming Stories, like Nganno the Giant and Tjilbruki, reveal deep ties to the landscapes, from the rolling hills and peppermint gum forests to significant sites like Parachilna Gorge.

The arrival of Europeans in 1837 marked a profound shift. While South Australia acknowledged Aboriginal land rights in the South Australia Act 1834, these rights were largely disregarded in practice, leading to dispossession, cultural fragmentation, and devastating population declines due to introduced diseases.

1840 to 1940 - Laying the wine foundations

Barossa was established soon after South Australia’s settlement in 1836. Surveyor General Colonel William Light named the valley after Spain’s Barrosa Ridge in Andalusia, where he fought in the Peninsula Wars of 1811. A clerical error resulted in the distinctive spelling of “Barossa.” English shipping merchant George Fife Angas played a key role in the region’s development, supporting the migration of free settlers, including a group of Silesian Lutherans led by Pastor August Kavel in 1842.

The Silesian settlers established themselves in Bethany, bringing farming expertise suited to Barossa’s Mediterranean climate. Their skills in agriculture, craftsmanship, and village-based industries helped shape the region’s economy. By the late 19th century, families such as Seppelt, Gramp, Smith, Salter, and Henschke had established winemaking enterprises. Fortified wines gained popularity overseas under Britain’s Imperial Preference policies, and by 1929, Barossa accounted for 25% of Australia’s wine production. However, the Great Depression and World War II led to a decline in demand, creating challenges for growers and producers.

1940's - Post-war reconstruction

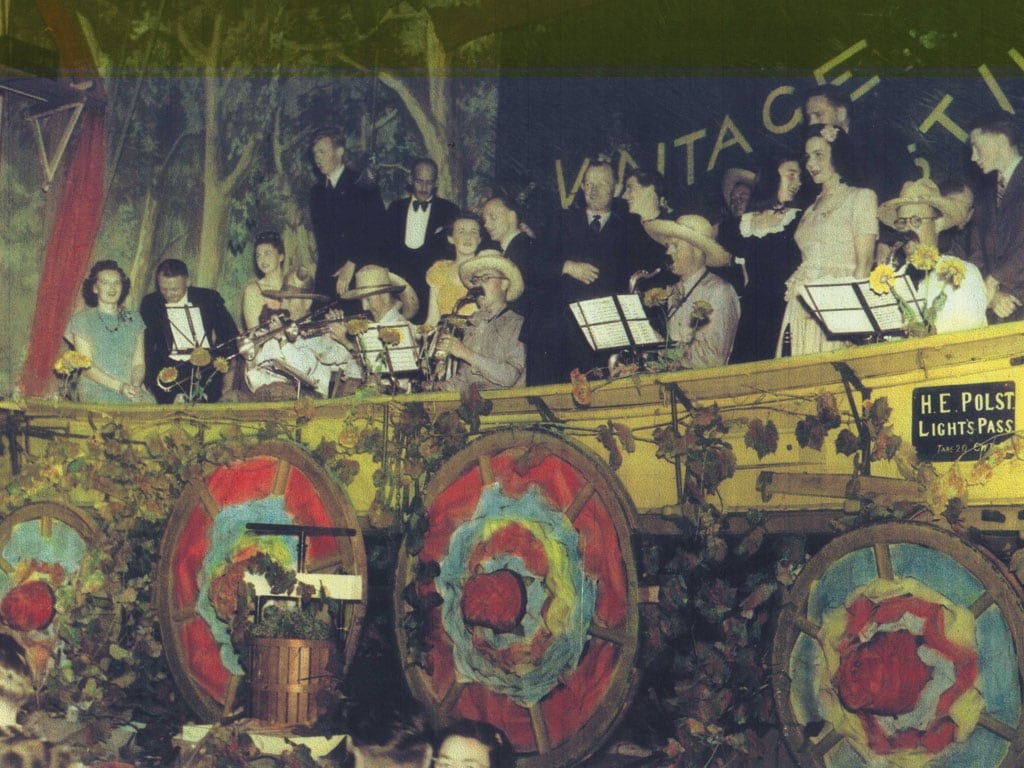

The aftermath of World War II brought significant change to Barossa. Tensions lingered between fourth-generation English descendants and their Barossan neighbours of German heritage, but the region’s first Vintage Festival in 1947 helped restore unity. A new co-operative movement emerged, taking over retail outlets and hotels, while efforts to modernise the local wine industry gained momentum.

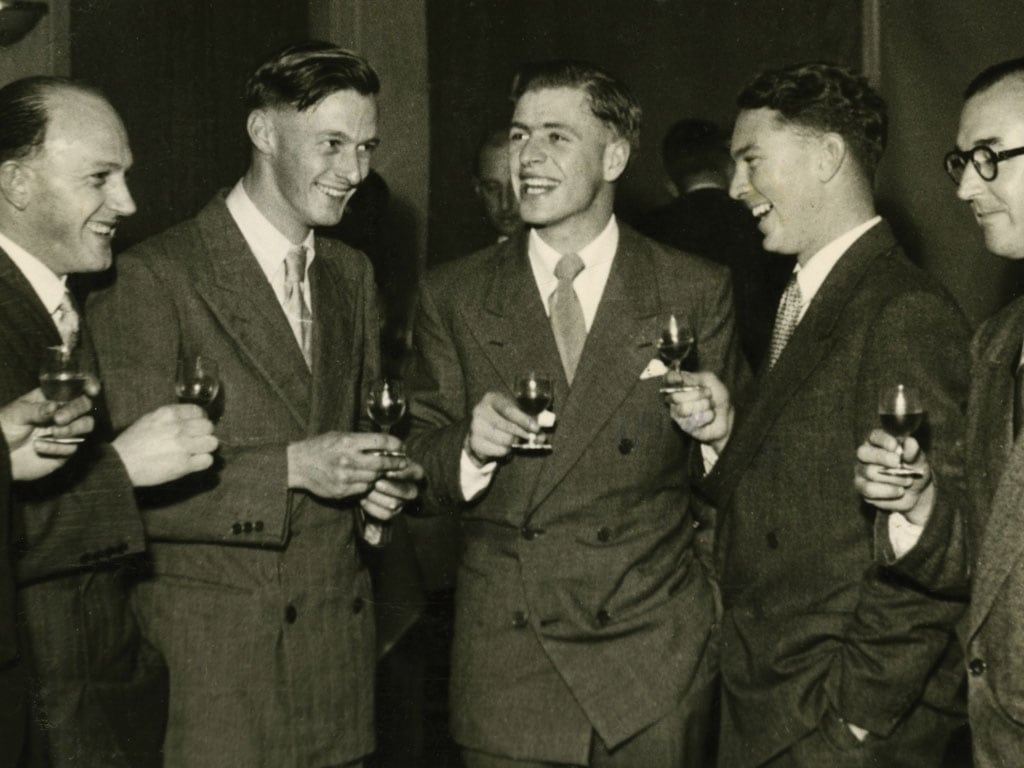

Colin Gramp, a descendant of Barossa wine pioneer Johann Gramp, returned from war via California’s Napa Valley, where he observed modern winemaking techniques. In 1947, he produced Barossa’s first dry red table wine in nearly a century—a Special Reserve Claret, predominantly Shiraz with some Cabernet Sauvignon. His innovations marked a turning point, shifting Barossa’s focus beyond fortified wines and establishing him as a key figure in the region’s transformation.

1950's - Optimism & innovation

The 1950s marked a new era for Barossa, defined by experimentation and progress. In 1951, Penfolds winemaker Max Schubert returned from Bordeaux inspired by the complexity of French table wines. Unable to source French oak, he instead matured Shiraz in American oak hogsheads, creating the first Grange Hermitage—a bold new Australian red that would shape the nation’s wine identity for decades to come.

Innovation extended beyond Grange. In the Barossa Ranges, Cyril Henschke crafted the first Mt Edelstone Shiraz in 1952, followed by Hill of Grace Shiraz in 1958. Meanwhile, Colin Gramp revolutionised Australian drinking culture with Orlando Barossa Pearl in 1956, using new techniques in secondary fermentation and cold stabilisation. Its popularity sparked a wave of sparkling wines – including Sparkling Rhinegolde, Pineapple Pearl, and Cold Duck – making wine more accessible to everyday Australians and, as some demographers claim, contributing to the 1950s Baby Boom!

1960's - Cool & elegant

While Australians were drinking an average of just two bottles of table wine per year, Barossa’s winemakers were leading a shift toward fine, cool-climate wines. Yalumba revived the historic Pewsey Vale vineyard in the Barossa Ranges, experimenting with high-altitude Riesling and Cabernet Sauvignon, while Orlando planted the steep, windswept Steingarten Riesling vineyard. Thomas Hardy & Sons introduced Siegersdorf Riesling, and John Vickery crafted some of Australia’s most celebrated Eden Valley Rieslings at Leo Buring.

In 1962, Penfolds released Bin 60A, a blend of Barossa Shiraz and Coonawarra Cabernet Sauvignon, which remains one of Australia’s greatest wines. Meanwhile, wine chemists Ray Beckwith and Tony Kluczko transformed winemaking with innovations in filtration and oxidation control, improving quality and consistency. In Angaston, a new star emerged – Peter Lehmann, who, after his Yalumba apprenticeship, took over as Saltram’s chief winemaker, crafting bold, long-lived “hydraulic press” Shiraz – it was the start of a career that would go on to reshape Barossa’s identity in the decades ahead.

1970's - Boom & bust

The 1970s saw a surge in red wine demand, driven by aggressive promotion from the Australian Wine Bureau and its director Len Evans. Barossa’s bold reds became the choice of Australia’s newly sophisticated wine drinkers, but many family-owned wineries struggled to scale up production. Several historic brands, including Orlando, Krondorf, Saltram, and Penfolds, were sold to multinational corporations such as Reckitt & Colman, Dalgety, and Tooths, who brought greater efficiency into the industry with mechanised grape harvesting and drip irrigation to guarantee consistent production. There is also less loyalty to the growers of the Barossa and without today’s strict regional integrity laws, cheaper fruit is sourced from the irrigated Riverland but still labelled Barossa.

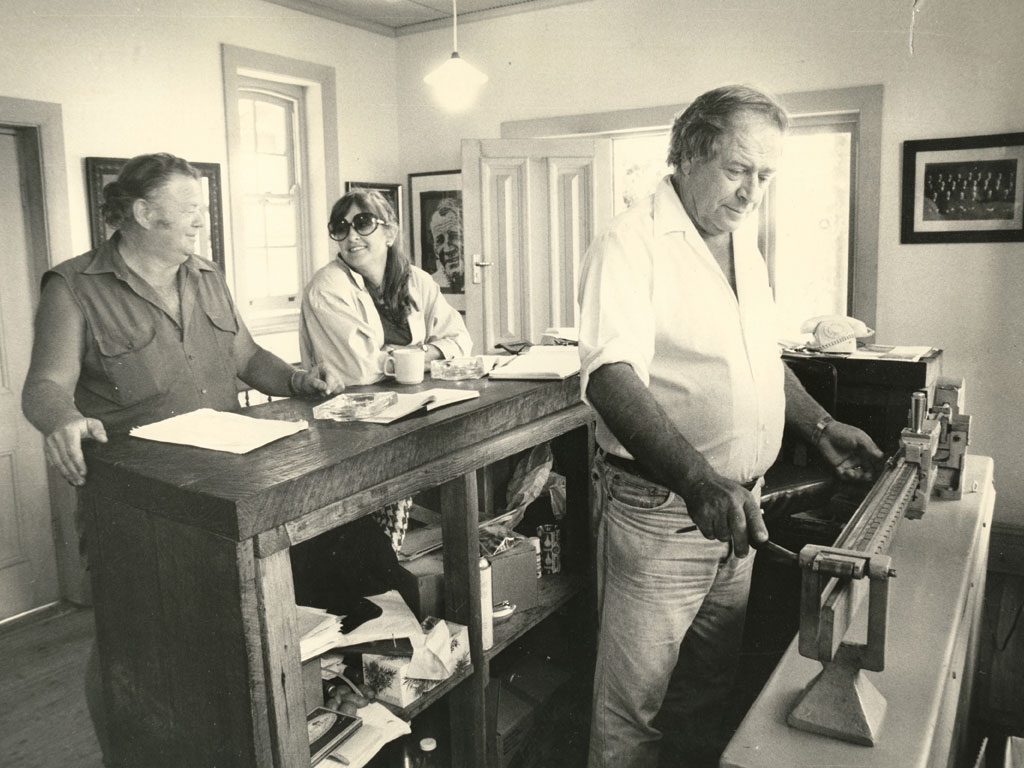

Innovation shaped the decade. In 1971, David Wynn invented the first bag-in-a-box wine container, later popularised by Orlando’s Coolabah Cask in 1974. Wolf Blass made history by winning the Jimmy Watson Trophy three years in a row (1974–76). However, by 1975, consumer tastes had shifted to fruity whites like Moselle and Chardonnay, triggering a red wine glut. When Dalgety ordered Saltram winemaker Peter Lehmann to stop buying fruit in 1978, he defied them, creating a grower pool to process surplus grapes. A year later, he left Saltram to start his own winery, securing a future for Barossa’s growers.

1980's - Out of the dark

The 1980s brought dramatic change to Barossa. In response to a grape oversupply, the South Australian Government introduced the Vine Pull Scheme, offering payments to growers who removed unproductive vines. The unintended consequence was the loss of century-old Shiraz and Grenache plantings, raising fears that Barossa’s agricultural land would be lost to housing development. With the regional grape crush in decline, some predicted Barossa would soon be reduced to vegetable farming.

Amidst this uncertainty, a new wave of winemakers emerged – many former growers determined to take control of their own fruit. St Hallett, Rockford, Bethany, Grant Burge, Charles Melton, Heritage, Willows Vineyard, and Elderton were among the wineries that opened cellar doors, following Peter Lehmann’s lead. Their success revitalised demand for old-vine fruit, introduced new wine styles and labels, and reignited tourism interest in Barossa’s food and wine culture. This was a massive structural change with a long-term impact on grape and wine prices, shifting Barossa from corporate dominance to a dynamic, independent wine community.

1990's - The revolution

The 1990s saw a bold shift in Barossa’s winemaking, with a confident return to traditional techniques such as basket presses and open fermenters. Instead of chasing the cool-climate styles favoured by wine judges in the 1980s, Barossa embraced its own identity—celebrating the provenance of old vines, the influence of soil and microclimate, and the pioneering legacies of Colin Gramp, Max Schubert, Cyril Henschke, and Peter Lehmann.

At the same time, UK Masters of Wine and global drinks media discovered Barossa, sparking an export boom that replaced years of oversupply. The region had evolved a style all of its own – full-bodied ripe Shiraz matured in American oak – which quickly won over consumers from Sydney to London and Los Angeles. Interest in heritage varieties like Grenache, Mataro, Riesling, and Semillon grew alongside Shiraz, and with demand soaring, growers could finally command profitable prices, allowing them to reduce yields, refine irrigation, and improve vine management – an approach that cemented Barossa’s reputation for premium wine.

2000's - Maturity: A new era for Barossa

As the new millennium dawns, Barossa rides the crest of an unsustainable wine boom. Rare, old-vine wines fetch up to $1,000 a bottle at US auctions, driven by global demand and influential critics. Growers receive record prices, some as high as $10,000 per tonne. But when global events shift focuses back to home, prices crash. Large wine corporations, which spent the ’90s acquiring historic labels, now turn to aggressive discounting. A global oversupply, changing consumption trends, and a monopolised retail sector push the industry into unprofitability.

Yet, Barossa’s story is one of resilience. As corporate giants retreat and speculators disappear, a new generation of winemakers and growers, now in their 30s and 40s, steps forward. Many are the sons and daughters of the revolutionaries of the 1980s, committed to wines of integrity and provenance. They refine styles, experiment with blends, and remain loyal to the growers who shaped the region.

By the decade’s end, Barossa is reborn – not just as a place of history, but as a region driven by craftsmanship, authenticity, and a deep connection to the land.

2010's - Hope & optimism

A new decade dawns, bringing a renewed sense of optimism for Barossa’s winemakers and growers. After years of global oversupply, the breaking of the drought and a “normal” 2010 vintage signal a long-awaited turnaround. But the biggest opportunities lie beyond Australia—particularly in Asia, where a rapidly Westernising middle class is embracing European and Australian wine.

As Australia’s most recognised wine region, Barossa is poised to benefit from this growing interest. The decade is set to be defined by profile-raising tastings, exclusive dinners, and brand launches from Shanghai to Seoul. A new generation of winemakers, much like their predecessors in London and Los Angeles, hit the pavement—only now, it’s The Bund and Beijing’s top restaurants where they pour, educate, and connect.

With shifting global demand and Barossa’s reputation stronger than ever, the region embraces new markets, fresh ideas, and evolving wine styles. It’s an era of reinvention—one that will shape the next chapter of Barossa’s story.

2020's - Reinvention & resilience

The world changes practically overnight, yet Barossa’s winemakers and growers meet the moment with characteristic determination. The loss of the China export market, compounded by COVID-19, forces a shift—but in true Barossa style, the community pivots.

As digital connection becomes the new norm, winemakers take to Zoom, hosting tastings and live chats while Barossa wines are poured at dining tables and home offices worldwide. This unfiltered, behind-the-scenes storytelling resonates, shifting how people engage with Barossa. Marketing campaigns embrace this shift, unapologetically people-first, celebrating shared values and the region’s down-to-earth spirit.

Adverse weather in 2021 and 2022 leads to significantly lower yields, but the wines prove exceptional – elegant, structured, with remarkable depth and length. As 2025 approaches, sustainability is no longer a concept but a necessity. Vineyards focus on soil health, water conservation, and regenerative farming, while winemakers embrace minimal intervention, organic practices, and lighter packaging. Barossa’s future is built on resilience, ensuring its wines and landscapes thrive for generations to come.